Copyright © 2013 CanineCancer.org.au All rights reserved.

Pathology

If it’s worth taking off; it’s worth looking at! The vital role of pathology in managing your dog’s cancer.

By Dr Rachel Allavena. Specialist Veterinary Pathologist. The University of Queensland School of Veterinary Science.

Having your pet diagnosed with cancer is worrying and stressful. Your veterinarian or veterinary specialist will often discuss with you having pathology done to aid them treating your dog or cat. Veterinary treatment can be expensive and it is tempting to not do pathology to save money. I’ve heard pet owners remark ‘Well it’s off now, it doesn’t matter what it is because it won’t change anything’. This is not true. Unfortunately, not doing pathology severely limits your pet’s treatment options and may impact their ability to fight cancer.

Why is pathology so important? Firstly, let me explain what pathology is used for and how it is vital to managing your pet’s cancer. Pathologists are expert diagnosticians. We have two roles; determining what the cancer is (called a diagnosis) and how it will behave (called a prognosis). Diagnosis and prognosis are essential as many cancers have well characterised behaviours and weaknesses which can be vital in selecting the best treatment. Pathology is the ‘gold standard’ for diagnosis. Specialist veterinary oncologists (vets who specialize in treating cancer) say it is not possible to correctly identify a cancer from looking at it in a veterinary surgery-

Cancers are classified as benign or malignant. Benign cancers are generally not life threatening. They may be easily treated or removed so your pet returns to full health. Malignant cancers on the other hand are life threatening. Their behaviours include invading into and destroying healthy tissues or spreading throughout the body (a process called metastasis); so must be removed or treated quickly to give your pet the best chance of recovery. With some malignant cancers a cure may not be possible, however effective treatments can maximise your pet’s welfare and survival often prolonging their life for years. Further, some types of cancer only respond to certain treatments, like specific chemotherapies, so without a diagnosis your vet will not know which medicines are appropriate. When the pathologist gives the diagnosis and prognosis, your vet will know the treatment to maximise your pet’s chances of survival.

What tests does a pathologist do? There are two major tests that pathologists run to diagnose cancer; cytology and biopsy (sometimes called histopathology).

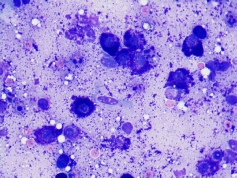

Cytology (the study of cells) involves examining cells removed from the cancer with a needle (called a fine needle aspirate or FNA) to see what type of tissue has caused the tumour. Cytology is relatively inexpensive, can often be done without an anaesthetic and with minimal distress to your pet. The cells are placed on a glass slide and stained with special dyes to allow the pathologist to look at their shape and features using a microscope. Cytology allows the pathologist to distinguish cancer from other diseases which might look like cancer, such as infections. When cancer is present the pathologist is often able to determine the broad classification of cancer (mesenchymal/sarcoma, epithelial/carcinoma or round cell tumour) which is important in deciding treatment options, as well as whether the tumour is benign or malignant. For some cancers the cytology diagnosis can be more specific, particularly mast cell tumours, melanoma or lymphoma which are common in dogs. Cytology is often the first step recommended by your veterinarian in diagnosing and managing your pet’s cancer.

Unfortunately, cytology has limitations. Some tumours don’t lose their cells easily so there might not be enough material for the pathologist to look at. Also the tissue structure of the cancer is absent, so it may not be possible to get a final (often called a definitive) diagnosis, or for the pathologist to ‘grade’ the tumour. Finding out the grade is a vital step in figuring out the prognosis, because the grade is linked to how aggressive the cancer is.

Cytology from a dog’s mast cell tumour. This is a fine-

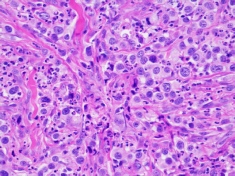

Biopsies Because of the limitations of cytology, your vet will often recommend doing a biopsy; either after cytology or as a first step. Biopsies involve processing one or more pieces of surgically removed cancer and looking at them with a microscope. Because the pathologist has more cells to look at, and the arrangement of the cells and their interaction with normal tissue can be assessed, biopsies provide much better information than cytology. Biopsies come in two varieties. Your veterinarian will recommend which is the most appropriate type of biopsy for your pet.

1. Incisional biopsies are when a small piece of the tumour is sampled purely to establish the diagnosis and prognosis. For example an incisional biopsy is appropriate if the cancer has spread, but options for chemotherapy or radiotherapy exist for treatment, for example lymphoma

2. An excisional biopsy is when the entire tumour is cut out in an attempt to cure the animal by surgery alone, for example soft tissue sarcomas or mast cell tumours.. On receiving an excisional biopsy, the pathologist will examine the boarder of normal and abnormal tissue removed by the surgeon (called the surgical margin) and let the vet know if they successfully got the entire tumour. If your vet has elected to remove the entire tumour it is vital that this examination is performed. Sadly this is often the time when pet owners think it isn’t worthwhile doing pathology. If some of the tumour has been missed at the first surgery it is frequently possible for another curative surgery to be done, called a wider excision, or for additional treatments like radiation or chemotherapy to go in and finish off the cancer. Unless the vet knows some tumour has been missed they won’t know to do these treatments. The greatest regret of pet owners who don’t get pathology done is missing out on the chance to cure a cancer because examination of an excisional biopsy was not performed. By the time the reoccurrence of the cancer is detected it is often too late to do any further treatments and a beloved pet is lost.

I

Biopsy (histopathology) from a dog’s mast cell tumour (high grade). Features like the rate of cancer cell division, and invasiveness of normal tissue allow the pathologist to ‘grade’ the tumour and predict its behaviour. The ‘completeness of excision’-

Immunohistochemistry and Immunocytochemistry

Another test that pathologists perform is immunohistochemistry (performed on tissues) or immunocytochemistry (performed on cells) using special antibodies to identify proteins present in the cancer which allow it to be identified accurately. Some cancers are so aggressive that they have lost the usual appearance that allows the pathologist to give a definitive diagnosis, called anaplasia. Fortunately, this situation is rare-

Thus, if it is worth taking off it is worth looking at. Although pathology tests are an extra expense; the value they provide to helping your vet successfully manage your pet’s cancer is immeasurable. For the best outcome possible, opt for allowing your vet to send off the recommended pathology samples to ensure your pet has the greatest opportunity to beat their cancer.

About the author: Dr Rachel Allavena BVSc(hons), BVBiol, GCHEd, GDip (anatomic pathology), MANZCVS, PhD, DACVP is a board-